Unlocking History, Philosophy, and the Foundations of Western Thought

In a world increasingly dominated by the rapid evolution of digital languages and fleeting online trends, the study of ancient Greek might seem like a niche pursuit, relegated to dusty university halls and obscure academic journals. Yet, the impact of the Greek language is far from relegated. It is a foundational pillar of Western civilization, an intricate key to understanding centuries of intellectual, political, and artistic development, and a surprisingly relevant tool even today. This article explores why Greek matters, who should care about its study, and what enduring value it continues to offer.

Why Greek Still Matters in the 21st Century

The significance of studying Greek lies not in its direct utility for daily communication, but in its profound influence on language, thought, and culture. Many of the words we use daily, particularly in scientific, medical, and philosophical contexts, have direct roots in Greek. Understanding these etymologies provides a deeper grasp of their precise meanings and the historical development of ideas. Beyond vocabulary, Greek was the vehicle for some of the most influential philosophical treatises, epic poems, and dramatic works ever created. Engaging with these texts in their original form offers an unparalleled window into the minds of thinkers who shaped the trajectory of Western thought, from Plato and Aristotle to Homer and Sophocles.

Furthermore, the grammatical structure of Greek itself presents a unique challenge and reward. Its complex declension and conjugation systems, while daunting, cultivate a rigorous approach to language and logic. This mental exercise can enhance analytical skills and a nuanced understanding of sentence construction, which proves beneficial in any field that demands precision and clarity. For individuals interested in linguistics, classics, theology, philosophy, or even the history of science and medicine, the study of Greek is not merely an academic pursuit but an essential pathway to deeper knowledge and appreciation.

The Historical Tapestry: Greek’s Genesis and Golden Age

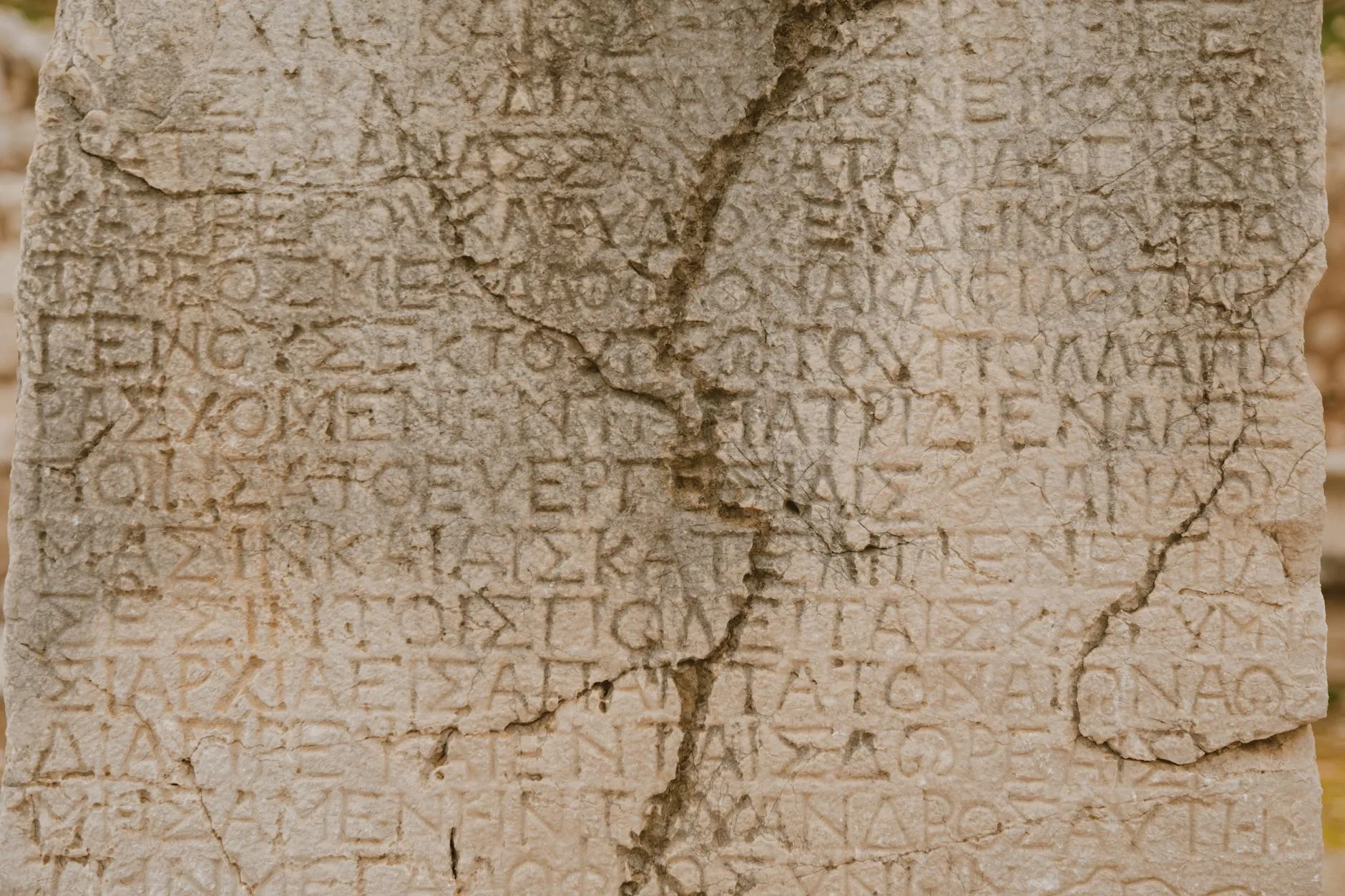

The story of the Greek language begins with its earliest attested forms, tracing back to Mycenaean Greek, written in the Linear B script, around the 15th century BCE. However, what most scholars refer to when discussing Greek as a foundational language is Attic Greek, the dialect spoken in Athens during its Classical period (roughly 5th to 4th centuries BCE). This era witnessed an unparalleled flourishing of literature, philosophy, and political thought, cementing Greek’s status as the language of intellectual innovation.

The development from Proto-Greek to the various dialects, including Ionic, Doric, and Attic, reflects the geographical and historical fragmentation of ancient Greece. The rise of Athens as a cultural and political powerhouse led to Attic Greek becoming the prestige dialect, eventually evolving into Koine Greek (common Greek) after the conquests of Alexander the Great. This Hellenistic Greek, spoken from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE, is the language of the New Testament and a vast body of literature that bridged cultures across the Mediterranean and beyond.

The influence of Greek extended far beyond the Hellenistic world. The Romans, deeply admiring of Greek culture, adopted and adapted much of it, including the language. Latin absorbed a substantial number of Greek loanwords and was heavily influenced by Greek syntax and literary conventions. This linguistic and cultural transmission ensured that Greek ideas and expressions continued to permeate Western thought for centuries, even as Latin became the lingua franca of the Roman Empire and later, medieval Europe.

The Pillars of Thought: Philosophy and Rhetoric in Greek

The philosophical revolution that took place in ancient Greece owes its existence and clarity to the expressive power of the Greek language. Thinkers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle developed intricate systems of thought, and their writings remain foundational to Western philosophical discourse. Plato’s dialogues, for instance, are not merely philosophical arguments but literary masterpieces, employing the nuances of Greek to explore complex ideas about justice, knowledge, and reality. Aristotle’s extensive works on logic, ethics, metaphysics, and science established terminology and analytical frameworks that are still in use today.

The very terms we use in philosophy are often direct translations or transliterations of Greek words. “Philosophy” itself, from philosophia (φιλοσοφία), means “love of wisdom.” Concepts like “ethos” (ἦθος – character), “logos” (λόγος – word, reason, account), “psyche” (ψυχή – soul), and “theoria” (θεωρία – contemplation) are all Greek in origin, each carrying a rich historical and conceptual weight that is best appreciated in its original context.

Rhetoric, the art of persuasive speaking, also reached its zenith in ancient Greece, with figures like Demosthenes and Isocrates demonstrating mastery of the language. The sophisticated use of grammar, syntax, and figures of speech in Greek rhetoric laid the groundwork for the study of persuasive communication that continues to this day. Understanding the structure and vocabulary of Greek allows for a deeper appreciation of these rhetorical strategies and their persuasive impact.

From Epics to Medicine: Greek in Literature and Science

The literary heritage preserved in Greek is immense and continues to captivate readers and scholars. Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are not only foundational works of Western literature but also invaluable historical and cultural documents. Their intricate narratives, vivid imagery, and profound exploration of human nature are best experienced in the original Greek, where the meter, wordplay, and stylistic devices contribute significantly to their power.

The dramatic traditions of Athens, exemplified by the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, and the comedies of Aristophanes, offer profound insights into ancient Greek society, its values, and its conflicts. The poetic and dramatic structures, the use of chorus, and the exploration of universal themes are all deeply embedded within the Greek language and its cultural context.

Beyond the humanities, Greek has an undeniable legacy in the sciences and medicine. Hippocrates, the “father of medicine,” wrote his treatises in Greek, establishing principles of medical ethics and observation that still resonate. Many medical terms derive directly from Greek: “cardiology” (καρδία – heart), “neurology” (νεῦρον – nerve), “dermatology” (δέρμα – skin), and “pediatrics” (παῖς – child). Similarly, scientific terminology in fields like biology, physics, and astronomy is replete with Greek roots. For example, “biology” itself is a compound of Greek bios (βίος – life) and logos (λόγος – study). Understanding these etymologies provides a more precise and immediate understanding of the scientific concepts they represent.

Perspectives on the Practicality and Challenges of Greek Study

The perceived difficulty of Greek is a frequent subject of discussion. Its inflectional nature, with complex noun and verb endings, requires significant memorization and analytical effort. This is a valid tradeoff; mastering Greek demands dedication and a commitment to rigorous study. However, this challenge is precisely where much of its value lies. The cognitive benefits of learning such a structured and inflected language are significant, enhancing a learner’s ability to grasp complex grammatical structures in any language and improving logical reasoning skills.

Some argue that modern translations and scholarly analyses offer sufficient access to Greek texts, rendering original language study unnecessary for most. While translations are undoubtedly valuable tools, they are inherently interpretations. The subtle connotations, the precise word choices, the rhythmic flow, and the cultural allusions embedded in the original Greek can be lost or altered in translation. As the renowned classicist E.R. Dodds once stated, translations are like kissing your sister: they’re close, but not quite the real thing.

Another perspective highlights the interdisciplinary nature of Greek study. It rarely exists in isolation. Those who study Greek often engage with Latin, history, philosophy, art history, and theology. This integrated approach allows for a richer, more contextualized understanding of the ancient world and its lasting impact. The knowledge gained is not just linguistic but historical, philosophical, and cultural.

Tradeoffs and Limitations: What You Gain and What You Sacrifice

The primary tradeoff in undertaking the study of Greek is the significant investment of time and intellectual energy required. Compared to learning a modern, analytic language, Greek presents a steeper learning curve. This time commitment might be a limiting factor for individuals with demanding schedules or those seeking immediate practical communication skills.

Furthermore, fluency in reading Greek does not automatically confer the ability to speak or understand spoken Greek with the same ease. While ancient Greek pronunciation has been reconstructed with a reasonable degree of accuracy, the primary focus of most academic study is on reading comprehension, particularly of literary and philosophical texts. This is a limitation for those who might hope to engage in spoken discourse or historical reenactment.

The value of Greek can also be subjective and context-dependent. For a student of ancient philosophy or a theologian studying early Christian texts, the value is immense and directly applicable. For someone seeking to become a software engineer or a primary school teacher with no specific interest in the humanities, the direct practical application might be minimal, though the cognitive benefits would still be present.

Navigating the Landscape: Practical Advice for Aspiring Greek Scholars

For those contemplating the study of Greek, a few practical steps and considerations can pave the way for a rewarding experience:

- Define Your Goals: Are you interested in reading philosophy, studying the New Testament, exploring Homer, or simply enhancing your cognitive abilities? Knowing your objective can help you focus your learning.

- Start with a Reputable Textbook: Many excellent introductory Greek textbooks are available, often designed for beginners. Look for those that emphasize clear explanations, ample practice exercises, and a gradual introduction of grammatical concepts.

- Embrace the Grammar: Greek grammar is foundational. Dedicate time to understanding noun declensions, verb conjugations, and sentence structures. Flashcards and consistent review are invaluable.

- Read Regularly: As soon as possible, begin reading simplified texts and gradually move towards authentic passages. The more you read, the more comfortable you will become with the language.

- Utilize Resources: Dictionaries, online forums, and study groups can provide invaluable support. Don’t hesitate to ask questions or seek clarification from more experienced learners or instructors.

- Consider a Teacher or Course: While self-study is possible, guided instruction can significantly accelerate progress and prevent the formation of bad habits. University courses or online Greek classes are excellent options.

- Be Patient and Persistent: Learning Greek is a marathon, not a sprint. Celebrate small victories and don’t get discouraged by challenging concepts. Consistent effort over time yields the greatest rewards.

Cautions: Be wary of programs or claims that promise rapid fluency without significant effort. The learning process for Greek is inherently demanding. Ensure that any resources you use are academically sound and reputable.

Key Takeaways on the Enduring Value of Greek

- Linguistic Foundation: Ancient Greek is a primary source for much of Western vocabulary, particularly in academic, scientific, and philosophical fields.

- Intellectual Heritage: It provides direct access to foundational texts in philosophy, literature, and science, allowing for deeper understanding than translations alone.

- Cognitive Development: The study of Greek’s complex grammar enhances analytical skills, logical reasoning, and linguistic precision.

- Cultural Immersion: Engaging with Greek texts offers unparalleled insight into the values, thought processes, and cultural achievements of ancient civilizations.

- Interdisciplinary Connections: Greek study naturally integrates with history, philosophy, theology, and linguistics, enriching understanding across multiple domains.

- Enduring Relevance: Despite its age, the conceptual frameworks and linguistic building blocks provided by Greek continue to shape modern thought and discourse.

References

- Perseus Digital Library: Perseus Digital Library. This is a comprehensive collection of ancient Greek and Roman texts, dictionaries, and tools, providing direct access to primary sources.

- The Greek Old Testament (Septuagint): Septuagint. An excellent resource for studying Hellenistic Greek, the language of the Old Testament in its Greek translation.

- The New Testament in the Original Greek: While scholarly editions vary, resources like the Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece provide critical editions of the Greek New Testament, fundamental for theological and linguistic study.